Family History

I must have got started with family history shortly after I left the RAF and have to say that it can easily take over your life. As many people do, I started by collecting names from the internet using a variety of sites but not paying too much attention to the possibility of errors being contained within other people’s research and trees. I did find, amongst my mother’s effects, a chart containing a huge number of names associated with the WAMPACH family who came from Luxembourg. This chart was handwritten by my Great Aunt Hazel SMITH who I never met, probably because she lived for many years in Canada although she died in Surrey in 1966. It is an unfortunate fact that I knew none of my Mum’s family apart from her Mum, Bessie and Auntie Violet and her second husband, Colin WEBB. As Mum died in 1963, I never had the chance to ask her all those questions that would have helped identify all those relatives and friends in the photograph albums that I have inherited.

|

23rd November 1940

Wyn SPITTY-JONES

|

|

November 2001 - Strood, Kent

Wyn GAY & John TURNER

|

|

2001

Michael and Helen SMITH

|

|

2012 - The HOOPER sisters:

Sheila, Barbara & Margaret

|

|

| Oct 1914 Bessie & Betty SCHMITT |

Whilst considering my Mum’s family, it is worthwhile having a quick look at her mother’s early life. Bessie JONES was the oldest of eight children born to John Robert JONES and Caroline Ann WEEKS. Mind you her parentage could possibly be disputed as she was born in November 1886, whilst John and Caroline married in January 1887. Her early life may have been an interesting conversation to have with her but I know only what I have gleaned from the censuses and some letters that I have. In 1911 she was 24 and a servant in Folkestone, but by September 1913, she was married in Exeter, Devon. How and why she went to Devon is unknown but it seems likely that she and her sister Fanny went there to work. Fanny subsequently stayed in Devon where she married and settled down.

|

2011

The Rolle Flats, Budleigh Salterton

|

|

1870

The Rolle Arms Hotel, Budleigh Salterton

|

|

2002 - Site of the Gerston Hotel

|

In 2002, the Gerston would appear to have become ‘QS’ and Superdrug shops whilst the Rolle Hotel has been demolished and become the Rolle Flats. Neither is a great improvement architecturally although I do note that in Paignton, the roof line seems to have been maintained. Unfortunately I took the photograph shown from the wrong side.

In 2002, the Gerston would appear to have become ‘QS’ and Superdrug shops whilst the Rolle Hotel has been demolished and become the Rolle Flats. Neither is a great improvement architecturally although I do note that in Paignton, the roof line seems to have been maintained. Unfortunately I took the photograph shown from the wrong side.

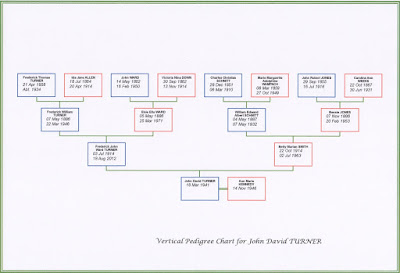

For my Pop’s family, it was a little easier because he was still alive but even he did not know as much about his extended family as I would have liked. My task on the TURNER side of the family has been made much easier because a large proportion of his ancestors came from Kent and the Kent Family History Society has a plethora of information that I have been able to tap into. They also have a thriving on-line section with a huge number of helpful and knowledgeable members.

|

July 2013 - Roseveare House

Sylvia WOODFORD, Kitty,

Maria, John & Ray TURNER

|

As I looked further back in time, I came across the HILLS family and made contact with Stan NEWPORT, who is a 4th cousin. The quantity of information that he was able to give me was quite phenomenal. We met up once in his home in Cheltenham and spent a very pleasant couple of hours chatting about our families. Our common ancestor is Mary Ann HILLS, born in 1824, who is my Great Great Grandmother.

Through the internet I made contact with Rebecca WARD, who is a 5th cousin, living in New Zealand. She has a massive amount of information about the ALLEN family who emigrated to new Zealand in the 19th century. More about George ALLEN to follow later. My closest ALLEN relative would be Ida Jane, my Great Grandmother

There are a few interesting people in my tree and I have written down parts of their stories where I am certain of the facts.

Edith WEARNE.

According to my Family Tree software, Edith is the second Great Grand Niece of my 4th Great Grand Aunt. She married Thomas Clinton PEARS, of the ‘Pears’ soap family. They were First Class passengers on the ‘Titanic’ when she sunk. Thomas did not survive but Edith did, having been rescued in lifeboat number 8. She went on to marry Douglas Valentine CROWE and have three children. She died in 1956, aged 66.

According to my Family Tree software, Edith is the second Great Grand Niece of my 4th Great Grand Aunt. She married Thomas Clinton PEARS, of the ‘Pears’ soap family. They were First Class passengers on the ‘Titanic’ when she sunk. Thomas did not survive but Edith did, having been rescued in lifeboat number 8. She went on to marry Douglas Valentine CROWE and have three children. She died in 1956, aged 66.

Josef DYGRYN, DFM.

Josef was born in Praha, Central Bohemia, Czech Republic in 1918 and married Doris Gwen Emily REEVES, who was my sixth cousin, on 7th Sep 1941. He was killed over the English Channel on 4th June 1942 and, when his body was eventually found, he was buried with full military honours at Westwell Burial Ground, Kent. Doris developed Tuberculosis shortly after her marriage and died in January 1942, aged just 20. A full history of Josef, which is well worth reading, is at:

Josef was born in Praha, Central Bohemia, Czech Republic in 1918 and married Doris Gwen Emily REEVES, who was my sixth cousin, on 7th Sep 1941. He was killed over the English Channel on 4th June 1942 and, when his body was eventually found, he was buried with full military honours at Westwell Burial Ground, Kent. Doris developed Tuberculosis shortly after her marriage and died in January 1942, aged just 20. A full history of Josef, which is well worth reading, is at:http://fcafa.wordpress.com/2010/07/24/josef-dygryn

Olive Mary MEATYARD.

Olive was the daughter of George MEATYARD, a jeweller, and Caroline Ann PAINE and is the second Great Grand Niece of my 4th Great Grand Aunt. She is described as an Actress on the 1911 census. In 1913 she married Lord Victor William PAGET with whom she had two children. They divorced in 1921 and in 1922 she married Henry Charles Ponsonby MOORE, the 10th Earl of Drogheda. She died in 1947 and on the death register she is named as Olive M DROGHEDA (Countess).

Olive was the daughter of George MEATYARD, a jeweller, and Caroline Ann PAINE and is the second Great Grand Niece of my 4th Great Grand Aunt. She is described as an Actress on the 1911 census. In 1913 she married Lord Victor William PAGET with whom she had two children. They divorced in 1921 and in 1922 she married Henry Charles Ponsonby MOORE, the 10th Earl of Drogheda. She died in 1947 and on the death register she is named as Olive M DROGHEDA (Countess).

Sir Godfrey Marshall PAINE, KCB, MVO

A fourth cousin, four times removed, Godfrey was invested as a Member, Royal Victorian Order on 11th March 1906. He was invested as a Companion, Order of the Bath in 1914. He gained the rank of Senior Commander in the service of the Royal Naval Air Service. He was invested as a Knight Commander, Order of the Bath on 12th March 1918. Born on 21st november 1871, he died on 23rd March 1932 aged 60. He was first Commandant of the Central Flying School (CFS) at Cranwell between 1915 and 1917. The CFS is the longest serving flying school in the world. It was formed on 12th May 1912 at RAF Upavon, it was an essential element of the Royal Flying Corps, which also consisted of a Military Wing, a Naval Wing, a reserve and the Royal Aircraft Factory at Farnborough. The cost of CFS was borne equally by the Army and the Navy but its administration was the responsibility of the War Office. The First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, informed Godfrey that if he wished to take up the appointment he had two weeks in which to learn how to fly! Godfrey was also Fifth Sea Lord and Director of Naval Air Service between 1917 and 1918 and Inspector General of the RAF in 1919.

A fourth cousin, four times removed, Godfrey was invested as a Member, Royal Victorian Order on 11th March 1906. He was invested as a Companion, Order of the Bath in 1914. He gained the rank of Senior Commander in the service of the Royal Naval Air Service. He was invested as a Knight Commander, Order of the Bath on 12th March 1918. Born on 21st november 1871, he died on 23rd March 1932 aged 60. He was first Commandant of the Central Flying School (CFS) at Cranwell between 1915 and 1917. The CFS is the longest serving flying school in the world. It was formed on 12th May 1912 at RAF Upavon, it was an essential element of the Royal Flying Corps, which also consisted of a Military Wing, a Naval Wing, a reserve and the Royal Aircraft Factory at Farnborough. The cost of CFS was borne equally by the Army and the Navy but its administration was the responsibility of the War Office. The First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, informed Godfrey that if he wished to take up the appointment he had two weeks in which to learn how to fly! Godfrey was also Fifth Sea Lord and Director of Naval Air Service between 1917 and 1918 and Inspector General of the RAF in 1919.

George ALLEN

George is a first cousin four times removed; he was born on 1st November 1814 and died on 10th May 1899. Our common Ancestor is his Grandfather, John ALLEN, my GGGG Grandfather.

George is a first cousin four times removed; he was born on 1st November 1814 and died on 10th May 1899. Our common Ancestor is his Grandfather, John ALLEN, my GGGG Grandfather.

Briefly, George was educated at Deal Academy and sent to Calais at an early age to learn French. At the age of 13, he was apprenticed to his father's partner as a boatbuilder and served his seven years. Following a lover's tiff with his eventual wife, he left home and travelled to Australia where he experienced sundry adventures including two shipwrecks. He returned to England in 1840. He married Jane PAUL at age 26 and they emigrated to New Zealand on the 'Catherine Stewart Forbes', arriving in Wellington on 11th Jun 1841. He established a successful Boat-Building Business until retiring in 1866 when he bought a farm at Lower Hutt which he passed onto his son Thomas eight years later. He then gave time to community and political life, including service on Wellington City Council and, for a brief period, served as Mayor of that city. He and Jane had four sons and five daughters.

The following is George’s own account of his parentage, birthplace and adventures. I have corrected spelling and grammar, to the best of my ability where appropriate but believe that I have kept the facts correct:

I was born in the seaport town of Deal, in the County of Kent, England. My parents, Geo. ALLEN, Master boat-builder of that place, was the son of John ALLEN of the Village of Walmer, a small yeoman farmer and fisherman, whose name has been known through his ancestors for many generations. His mother (Elizabeth GARDNER) was the daughter of a yeoman farmer and fisherman of the neighbouring Hamlet of Kingsdown, nearly under the shadow of the South Foreland Lighthouse. Both of the families were of good repute and of unquestionable honesty and reared a race of sturdy Kentish men and women. So much for my grandparents on my paternal side. On my maternal side my dear mother was left a widow by the death of my father at the early age of 45 years. My mother's name was Mary L SNOSWELL, the eldest daughter of Thos. SNOSWELL, a master mariner of the Port of Deal, who, in his early years served his country in the Royal Navy, and was present as a young seaman on board of HBM Sloop of War ‘Lively’ and took part in the Battle of Bunker Hill in Boston Bay when almost the first blood was shed in that contest which ended in the loss of the Colonial Empire in that part of America. Afterwards he served in the Royal Navy, under the command of Sir John JERVIS. For conspicuous gallantry on board of ‘HMS Foudroyant’ when the capture was effected of a French line of Battleship and safely took the prize, into Portsmouth Harbour, his Captain, Sir John JERVIS, afterwards the great Naval hero, the Earl of St. Vincent, offered to place him on the quarterdeck, or give him an Admiral's discharge. He married my maternal grandmother, a Kentish lass in the same state of life as himself. He settled down as a Master Mariner and owner of fishing craft, therefore throwing up what would, in all probability, have been an honourable and successful career under his old Commander in the Royal Navy of Great Britain. So much for my immediate forefathers, true and honest old Kentish sea dogs.

I must come to my somewhat erratic career in my early manhood. I passed the usual life of a schoolboy in my native town, where I was born on the 1st day of November, in the year of our Lord, 1814, and was the eldest of eight, three sons and five daughters. After doing pretty well at the Deal Academy, my father, knowing my wish to be a sailor, sent me over to France, to the seaport of Calais where I picked up a tolerable knowledge of French. I then returned to Deal, and, at the early age of thirteen years and six months was apprenticed to my father's partner James RATCLIFF, a celebrated and skilled tradesman. I was induced to alter my early inclination of going to sea on account of the failing health of my dear father, who died on the 15th day of April, 1830, after a very long and painful illness, after which sad event I stuck zealously to my trade and in short time there were few men in the establishment could beat me as a workman. I served my seven years truly and faithfully, with some of the disagreements of an apprentice, many times desirous of going to see the World of Waters, but, thanks to good advice, kept true to my engagement, and I am thankful to say I did, as I have found the possession of being a skillful mechanic a great boon. I have been enabled at a comparative early age to retire from working at my trade as a boat-builder and I have enjoyed many years of leisure in my old age. I became engaged to my dear wife who was Jane Elizabeth PAUL, but on account of a lovers' quarrel or tiff, I ultimately left Old England on the 21st day of May 1836. A narrative of my doings during the four years and five months of my absence from home will be briefly touched upon in this, my autobiography, and, as a departure will be taken, I will commence a new page.

On Saturday, the 14th day of May, 1836, I was busily employed finishing a whaleboat, when a neighbouring trader called at our boat building shop and enquired if any young man of our trade felt any inclination to accept an appointment under the South Australian Company as a boat builder, to proceed to Adelaide, South Australia. I, in an unguarded moment, undertook to leave all my friends and relatives, also my widowed mother, to my great disgrace, with a family of seven young children to battle the World, but, still under the protection of Mr James RATCLIFF, acting the benevolent part of a protector to mother and orphan family. This conduct on my part left an undying regret and I was well punished during my absence, in mind and body for my unfaithful behaviour to my widowed mother and family, a fatal mistake on my part.

Well, within one week of the undertaking, I was on board a small brig named the ‘Emma’ with Captain NELSON and a few more passengers, also indented servants of the above company. We proceeded on our voyage, I suffering very much from sea-sickness and remorse, but there was no help. I was launched on my way. We had a tedious voyage of several weeks to the Cape of Good Hope where we lay for twenty eight days taking in stores for the new settlement, pledging myself to return as soon as possible. I did so endeavour to do but the following narrative will explain the reason of my absence. We arrived at our destination on the 6th day of October, 1836, at Kangaroo Island, then in its wild state and found a few Company servants employed in erecting bush huts and living in tents until a better shelter could be provided.

South Kangaroo Island South Australia

My first duty on landing, with a young lad that left his home with me, was to erect some shelter, which we did out of scrub and Tee Tree. Here I commenced to work at my trade by repairing a whaleboat belonging to one of the Sealers resident on the Island, and afterwards I was employed in conjunction with another boat-builder, who arrived a few weeks after myself, in building several whaleboats for the fisheries about to be established on parts of the South Australian coasts, where the whales frequent in the Winter season and the fishing was successful. I was induced to go there for two months in the place of a man who was expected from Hobart Town but he did not arrive until the season was nearly over. On his arrival, I returned to Kangaroo Island and continued at my trade, also helping to repair one of the Company's whaleboats the ‘Sarah and Elizabeth’. Having finished her, I managed to get my discharge sometime in the month of November, 1837. I had an opportunity offered me to return home by an exchange with a carpenter of the ship ‘Solway’ of London, who desired to remain in the Colony whilst I desired to leave it. I joined the ship and in a week or two's time we sailed for Endeavour Bay, the site of one of the Company's whale fisheries, to take in about 200 tons of oil and whalebone, intending to go to Hobart Town to fill with wool. We arrived in the Bay alright and the next day were busily employed with the assistance of the whale men mooring the ship, but, through the refusal of our Captain to give the men a dram of rum before they commenced work hauling the ship under a bluff headland and mooring her to the rocks by the stern, the ship was left out in the open Bay and during the night a furious gale set in, the ship riding very heavily on her cables and with the two anchors, being laid for mooring purposes only, acting as a single anchor. Immediately inside us the surf was breaking furiously on a reef and we were in imminent danger of our lives, if the chains parted. At about 11 o'clock one of her anchor chains parted; the other chain brought the ship head to the sea. She therefore took the reef end on and when she struck, her stern frame was very much damaged and, after striking heavily for a few minutes, she dragged bodily onto the reef and filled full of water up to the hold beams. We had to take to the rigging to save our lives and for many hours we were in great danger, but at low tide the whalers came through the surf and got under the lee of our stern and we were enabled, some through the poop windows, some down the top lift of the spanker boom, to drop ropes into the whaleboats; ultimately we were all safely landed by the skill of the boatman, dropping in through the surf and landed in what we stood upright in, viz., a blue shirt and a pair of duck trousers; this happened on the 18th day of December, 1837. The next day being fine we were enabled to board the wreck. I found my clothes-chest, tool-chest, and bedding as I had left them when we left the ship, mine being fortunately in the weather side escaped loss and damage. Those on the lee side were totally destroyed by whale oil and other means from the salt water in the hold. The whalers to whom I was well known took all that I had and landed it for me first of all, and after that the Captain's goods, who was first to leave the ship. The ship was condemned on survey, and after fitting up the long boat we crossed the Straits to Kangaroo Island where I stayed for two or three weeks unemployed. The Company would have nothing more to do with me, however, another opportunity offered me by joining the ship ‘Sarah and Elizabeth’, the ship I helped to prepare. She having successfully shipped the oil in Encounter Bay, we started on our voyage to Hobart Town but had a very rough passage, the old ship leaking very badly. The Captain told me on one occasion of the serious leaks, that it would be a good job when we got into port as the ship was 60 years old by the present register, and that did not say when she was built, the Captain declared she was one of the Old Spanish Armada. She was an extraordinary bluff-nosed old ship and had a checkered career, as I had known her in my boyhood as a South Sea Whaler. We arrived at Hobart Town to our great joy, where the old ship was condemned for repairs and we were paid off. No opportunity offering in Hobart to proceed on my voyage home I went to work at my trade as a boat-builder. I was doing very well indeed, earning five pounds a week, and should have certainly stopped in Hobart as many inducements were held out to me to so, but, having made up my mind to go to Sydney by the first opportunity, I did so by falling in with a young lad of Deal, who got me a passage to Sydney in his ship, the ‘Bunney-Henry’ and, after a prosperous passage, landed in Sydney. I worked on board ship as a shipwright for some time and might have done well at my trade if I had stayed as a boat-builder, but, still being bent on going home, I had an opportunity of joining a very fine ship as carpenter called the ‘Orontes’, of London, laying in Sydney Harbour, bound in good time for Madras. After laying sometime in Sydney Harbour, Captain SHORT, got the charter to take the buildings and other stores required for a new settlement about to be formed in North West Australia at Port Essington. We left Sydney Harbour on the 17th Day of September, 1838, in company of ‘HMS Alligator’ and two merchantmen but had to take the unknown and dangerous passage known as Torres Straits. After a good deal of buffeting against a foul wind we caught the SE Monsoon and made our way through the Straits, keeping a good lookout for danger, the ‘Alligator’ most times leading the way, and after a passage of twelve days we cleared the straits and I must express my delight at the views that were daily offered us. The reef on which Captain Cook's ship ‘Endeavour’ struck, the Cape called Tribulation, with Endeavour River, where the ship was partly repaired, was brought to view by our Chief Officer, WW SIMPSON, a gentleman of great attainment who was a good friend to me. After leaving the Straits we hove off Booby Island; on Sunday I went ashore in our quarter boat to the barren rock, myriads of birds in the shape of Boobies filled the air as we landed, and after entering in the log book on the Island we re-embarked and proceeded on our journey and ultimately reached Port Essington on the 26th day of October, 1838. We anchored, and the work of discharging the cargo commenced, and in about seven weeks was completed. We then made sail for our destination, viz., Madras, on the 12th day of December 1838, but the second day after leaving the Inner Harbour and being then almost six miles from New Holland, we struck on an unknown reef and after boxing the yard for a few minutes the ship floated, but on sounding the pumps, found her in a sinking state having made two feet of water in about ten minutes. I reported the condition of the ship to the Captain who laughed at me for making such a report, but on being convinced by the Chief Officer of the state of affairs, asked me to give my opinion of what was best to be done. I recommended to square the yard and try to run the ship on shore before the water made her unmanageable, which course was taken and the ship ran on shore before the mainland of New Holland, after one and a quarter hours struggle at the pumps, we landed, and on sounding the well I found nine feet of water in the hold and everything we had on board under water in the hold, and before the seaman could get into the forecastle their chests were swimming. A boat was sent up the harbour to communicate the disaster to the Commodore, Sir Gordon BREMER. We had plenty of muskets but very little ammunition, and only the protection of a small deck boat surveying for the ‘Alligator’. We should have been in a very precarious state as we were surrounded the next morning by many canoes filled with blacks, well armed with spears and boomerangs, but fortunately before the attack was made the launch of ‘Alligator’ hove in sight, well manned and armed, and the blacks cleared out to our great joy. The ship was surveyed and condemned and after dismantling the ship we were embarked on board the ‘Brittomart’ and taken back to the Inner Port from whence we sailed so short a time back on our passage home via Madras. We were landed on the beach of the Inner Port with our chests and bedding without anything to eat on the first day of January 1839, a poor disconsolate body of ship-wrecked men not knowing what would be our next move. The Marines that came down with us took us to their encampment and gave us a share of their poor daily ration, and after that I interviewed the Commodore with the Boatswain, our Chief Officer who was our friend being on the sick list. Our Captain and Second Officer entirely abandoned us to the tender mercies of the Naval Authorities. I will briefly inform of our interview as follows:

We met the Commodore, Sir George BREMER, accompanied by his Purser, a gent with one arm. I briefly stated our case and necessities, telling him of the remarks made by Lieutenant STANLEY, commanding the ten-gun ‘Pieter Brittomart’ from which brig we had been so badly used, not having anything to eat for some hours and finding the softest place on the forecastle deck for my bed and the stalk of the anchor for my pillow. We briefly threw ourselves and our shipmates on the Officer Commanding as shipwrecked seamen and he immediately assumed the responsibility as his duty, informing us that he had no means of sending us to Sydney until some months might elapse before the ‘Alligator’ could leave for that Port, informing us that he could only allow us the Naval ration of one pound of flour, alternately with three-quarters of a pound of pork with one gill of peas and one pound of bread the next day, truly not a very brilliant lookout, for perhaps six months; it took us nearly seven months before we got clear of the Royal Navy, however, the Commodore informed us that if we were willing to work, he had no doubt that his influence with the Admiralty would be strong enough to get payment for our services that we might render. I immediately placed myself and my shipmates under his orders. He ordered the Purser to issue us the daily ration and told us to take what sails we required for our tents and erect one forthwith which we did and after several hours fatigue in the sun and mosquitoes, the heat at about 130 degrees in the sun, we finally succumbed at 12 o'clock. The old black cook having cooked our salt beef, we crept under partial shelter, ate our dinner with a good appetite, and when the sun got less powerful at about three o'clock went to work. We finished our tents and slung our hammocks and sat for a few hours in the gloaming listening to the frogs, the shrieking ...(missing)....... ourselves for duty, myself and the carpenter's mate. We were placed under the orders of the carpenter of the ‘Alligator’ and thence helped to build the houses and other lodgings required for the settlement, so the time crawled along. An opportunity having offered to myself to get the good grace of the Commodore, he having a very fine favourite six-oared galley of his own which had, fortunately for me, broken adrift and was found so badly damaged that the Warrant Officer of the ‘Alligator’ condemned her. The Coxswain, knowing me by repute as coming from Deal, got me to examine her. I immediately saw that she was repairable and undertook to repair her. I interviewed Sir Gordon and told him I could. He was highly delighted and said "go ahead" and I rebuilt her to his satisfaction. He told me, when I had finished that he had one more desire for me to work, as he was pleased to say I had earned my rations, and said he would take good care that such a report should be sent home to the Admiralty that would get me well paid for my services. He was as good as his word for after about fifteen months from the time of our return to Sydney, I applied to the Admiralty for my pay. I found to my great surprise he had awarded me the sum of £6:6:0 per month, the same as a Second Class Warrant Officer was entitled to in the Navy, with an additional eight shillings per month tool money. I received nearly £40 for my services rendered after the loss of our ship, the same wages as I had an board of the ‘Orontes’, therefore not losing a day's pay by the shipwreck, the ‘Orontes’ pay terminating on the 31st December, 1838, and the Navy pay starting an the 1st of January 1839, so all ended well up to our arrival in Sydney. I still continued to assist the carpenter's crew at repairing the boats and other duties until the order for embarkation came and we got up anchor at sunrise, made sail and started for Sydney. We arrived after a six weeks passage round the Cape Lewin.

On our arrival in Sydney Harbour, in July 1839, we moored ship and the next day fatigue parties of the Military stationed there came down to the landing place and carried up to the Hospital about fifty of the crew of the ‘Alligator’ who were stricken with scurvy, many of them in the last stage of the disease. The rest of the Crew were, more or less, myself included, suffering great pain in our limbs and languor, so much so that the Doctor told us that any of us that could stand the deck must do, so nearly all of us were fitter for the sick list than duty. However, after a few days on shore most of us were convalescent and the men in the Hospital improved daily and no deaths took place. We were mustered an the Quarterdeck the day after our arrival in Sydney, and a certificate of good conduct was given to all and we were complimented by the Commodore on our good behaviour whilst under his command. I was strongly recommended to join the Navy having been promised a Warrant Officer’s position if I would continue to serve. This I thankfully declined, the Commodore giving us to understand that a ration and shelter would be at our service for one month without any duty. We declined with thanks for his and his Officers' kindness to us during the time we were attached to the Navy. After landing and getting lodgings, myself and a shipmate named Thos. ROACH, kept idle for some time until an opportunity offered to proceed to England. An offer to join a large brig called the ‘Adelaide’, which vessel was about to sail for New Zealand to load timber for the Colony of Adelaide. Two of my shipmates joined the brig and ultimately our good Chief Officer of the ‘Orontes’ took command of the brig to our great satisfaction.

We sailed for New Zealand, calling at the Bay of Islands, landing cargo and a few passengers, again sailed for the Thames, but stopped at an Island called Waihake, where our Owner purchased a large quantity of large logs of timber (Kauri). We lay altogether nearly ten weeks in New Zealand living well on NZ food, pork potatoes, and fish. After completing loading, we proceeded on our voyage to Adelaide and after a very stormy passage of five weeks arrived at our destination, finding many old friends in Adelaide. We spent Xmas of 1839 in Adelaide, enjoying the hospitality of my old chums, and after spending a pleasant time sailed again for Launceston, then called Van Diemen’s Land, and shortly after our arrival commenced loading for London. It took us some time to fill up, and about the 24th March, 1840, proceeded down the Tamar and had a very narrow escape of shipwreck on our passage down, having struck a snag, we hung on until the ship's deck was at an angle of 45 degrees, the passengers and most of the crew were on the banks of the river when she suddenly slipped off into deep water and on sounding the well (repeatedly) found the ship making no water. We proceeded on our way down, the navigation of the Tamar was nearly all done by warping, a very tedious process there being no tugs in existence at that time. I am sorry to record the loss of my dear friend Thos. ROACH, who fell out of the main top overboard and never rose again, to my sorrow, as I was very much attached to him after being shipmates for nearly two years. We sailed on 1st April, 1840 with a fine fair wind, intending to go around Cape Lewin therefore cheating the Horn. We had made some hundreds of miles on our way when strong westerly gales met us dead ahead and finding that the ship had strained herself on the snag she began to take water very fast, and after a very stormy passage in the middle of the winter doubled Cape Horn on the 25th day of June, covered with ice and snow. The ship most of the time required pumping every hour. About fourteen days before leaving I was laid up with a very bad attack of Yellow Jaundice, it was nearly a case with me but fortunately we had a Doctor on board and I ultimately recovered and went to my duty after rounding the Horn. We then got into fine warm weather and arrived at Rio de Janeiro where we laid seven days. We took in water and other supplies and sailed again for Old England, and met a north-easter in the chops of the Channel, passing Deal on the morning of the 1st September, just five months on our journey home, and made fast in the Docks on the 3rd of September. I left the ship and went down to my Aunt and sister at Gravesend, and after settling up my affairs for wages &c., proceeded to Deal, met mother, brothers and sisters, not forgetting my old faithful sweetheart, Jane E PAUL, and once more in the home of my childhood after an absence of four years and five months, and there ends my adventures since I left my native land.

Geo. Allen.

Currently my Family Tree contains 11,892 names and, at present, I am trying to ensure that all those names are actually related to me, even if they are eighth cousins.

No comments:

Post a Comment